For millennia, humans have striven to understand the many wonders of the world, driven by an innate curiosity to learn and understand. In a time before modern technology provided easy methods of documentation, crafts like painting and drawing were the main techniques employed to catalogue any new findings. This collision between scientific investigation and creative practice has resulted in a stunning visual record of humanity’s exploration of the world.

Table of Contents

Where Art Meets Science

Covering a vast array of subjects, from mathematics and botany to chemistry and astrology, the symbiosis of art and science is woven throughout our visual culture. The natural sciences–the branch of science that deals with the physical world, provided an ample playground for creative expression when humans first endeavoured to understand the universe’s unknown wonders, with many of the early works that sit on the threshold where art meets science created on the broad subjects of natural history and philosophy.

This then evolved into niche topics as advances in the sciences were made and subjects were defined further. From an eighteenth-century investigation into the metamorphosis of butterflies to a vibrantly illustrated volume of ancient geometric theory, scientists have continuously used artistic methodologies to interpret their findings.

The Study of Natural History

Classical luminaries produced some of the earliest writings on the subject, with Pliny’s Naturalis Historiæ (1469) believed to be the first work on natural history to be published. European naturalists penned prolific volumes on subjects like botany and zoology, with Ulisse Aldrovandi even producing a book of monsters, titled Monstrorum Historia (1642), that documented the unnatural side of humanity.

Although these early volumes contain accounts of both realistic and fantastical specimens based on observations of the natural world and those found in mythological texts, these works were foundational in the development of natural study.

The Scientific Art of Leonardo da Vinci

The works of Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), are the perfect example of when art meets science. An Italian polymath of the High Renaissance, Leonardo explored diverse scientific fields, from human anatomy to engineering and astrology, in a relentless attempt to understand the workings of the universe. While he was hunting for the fundamental answers to life itself, he produced some of the most beautiful explorations of the sciences.

Driven by spiritual intention, Leonardo endeavored to understand man’s form and structure in line with the deeper meaning of human existence. Conducting over thirty human dissections in his lifetime, his eagerness to understand the human entity resulted in a compendium of anatomical drawing that also explored the philosophical idea of beauty.

The Art of Anatomy

Anatomy has long been of interest to those striving to understand the human entity. As time progressed through new periods, compendiums of drawings documenting anatomical discoveries were produced. Stretching across the centuries, these illustrations have proved invaluable in understanding the human form for both artists and scientists.

Similarly, those who followed him, like anatomists Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) and Charles Estienne (1504–1564), produced volumes of anatomy that featured elaborate illustrations of the body in varying poses and settings. These grand and aesthetically opulent volumes posed philosophical questions on the existence of man while also documenting his make-up.

Following the early expositions on the subject, modern studies of anatomy have populated medical teachings over the last few centuries. In alignment with the developments in science and medicine, cornerstone works like Gray’s Anatomy, published in the nineteenth century, presented human anatomy in a whole new light– one intended for the purposes of medical teaching, with clean, scientific illustrations to match.

The Art of Astronomy

Leonardo, however, was not the first to combine the fields of scientific observation and creative documentation in search of divine understanding. The establishment of astronomy centuries prior provided a promising method for visual explorations of the night skies.

The first documented records of astronomical observations date back to around 1000 BCE, with early astronomers building up their knowledge of the celestial bodies by charting their changing motions. The study of the heavens is regarded as one of the oldest natural sciences, deeply interwoven with spirituality, with early cultures understanding celestial events and objects to be divine manifestations, thus establishing the theological practice of astrology. In the centuries before the Copernican Revolution in the mid-sixteenth century, the coalescent exploration of cosmology left behind an assemblage of staggering observations of the heavens linked to the Gods.

It was during the Renaissance period that scientists Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) and Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) rejected religious theology and mapped a new astronomical understanding that revolved around the sun. They were branded heretics and punished for publishing their scientific discoveries against the church, yet their theories have gone on to form the foundation of modern astronomical practice.

Unlike Copernicus who only published his observations as text, in 1609 Galileo produced six watercolors documenting the phases of the moon ‘from life’ as observed through his telescope. This small collection of paintings represents the first realistic depiction of the moon and its phases in human history, capturing its beauty in delicate painted form.

Painting Nature

In 1831, Charles Darwin undertook a key expedition around the world on the HMS Beagle that would be pinnacle to the development of his theory of evolution. During his travels, he utilised a small colour book to help him identify the colours of the species he discovered, noting them down in his journal. Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours set the foundation for colour standardisation.

More modern visual treatises on subjects including entomology, ornithology, and botany were published, sharing new knowledge with new audiences. Works from the likes of the Bauer Brothers (Franz Bauer, 1758–1840, and Ferdinand Bauer, 1760–1826) popularised the Linnaeus system of biological classification through their beautifully illustrated volumes of the world’s plants and animals, spurring an uptake in interest in the natural sciences.

Women in Science

This marriage of artistry and science in the world of botany provided a new opportunity for women from the eighteenth century onwards. Deemed gentile in its nature, the study of plants was professed as an acceptable past-time for women, allowing them space in a scientific world typically governed by men. The subject’s popularisation acted as a catalyst for botanical discovery and documentation predominantly made by women, with many female scientists also producing stunning illustrative examples of their observations.

The artist naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717) catalogued her discoveries of butterfly, insects, and flower specimens through a mixture of painted imagery and stunning copperplate illustrations. Her work visually articulated the metamorphosis of butterflies and flowers, yet her vibrant insect portraits are as unique in their style, shape, and form as her entomological and botanical findings, imbuing her legacy with provenance in the worlds of both science and art.

Another female botanist, Anna Atkins (1799–1871), used an early method of photography when creating the first published book illustrated with to feature botanical photographs. Her groundbreaking volumes of cyanotypes showcased a new method of scientific documentation through vibrantly coloured Prussian blue impressions, with each specimen artistically reproduced in crisp white and blue prints. She was a pioneer of a new photographic process artfully blending the worlds of botany and photography.

Like many other female scientists working over the last few centuries, her contributions made to both the arts and sciences showcase the beauty found in the intersection between the two. Creating work from a new, feminine perspective, makers like Atkins and Merian often pushed the boundaries of traditional scientific documentation, utilising pioneering technologies and forging new paths of knowledge, perhaps as a rejection of the traditional oppression of women in the sciences.

The Theory of Colours

In the same vein that scientific discoveries have guided creative expression throughout the centuries, later artists have continued to produce works inspired by the sciences, often employing scientific theories in their artworks.

The cornerstone work of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and his Theory of Colours, published in 1810 laid the foundation for modern colour theory. Off the back of Isaac Newton’s 1704 book Optics, in which he formalised the first colour wheel commenting on the nature of primary colours, Goethe’s founding work on colorimetry created new instances of colour perception. This formalisation of colours was foundational to modern colour theory in a period before chemical advancements rapidly expanded the colour range, and Theory of Colours became a key ideology for artists and scientists alike.

Towing a lineage of both artistic and scientific development, Wassily Kandinsky’s abstract paintings were based on the concepts of colour theory, mathematics, and sound, investigating their ephemeral impact on the observer. A key colour theorist of the Bauhaus (the Weimar school of art and design, founded in 1919), his artistic ideologies leant into the arcane intellect that married sound and mathematical proportions, while also exploring their relationship with colour.

Geometry and Modern Art

Established in the aftermath of the First World War, the Bauhaus and its corresponding modern art movements took inspiration from Euclidean geometry, finding peace in the clean order of the mathematical proofs created by Oliver Byrne in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Byrne’s Elements of Euclid (1847) was the first attempt to illustrate the classic books of mathematical theorems produced by the ancient Greek mathematician Euclid of Alexandria, which were originally penned around 300 BC. In addition to proving fundamental in the teaching of geometry and mathematics in the following centuries, Byrne’s primary-coloured proofs hold a legacy of their own within the art world.

The hard geometric order inspired a stylised conformity in the wake of the war, with artists of the Bauhaus movement rebelling against chaos and destruction, looking for a return to order. The influence of Byrne’s crisp shapes and colours can be seen not only throughout Kandinsky’s practice, but also in the works of his contemporary Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) and his iconic, bold geometric masterpieces.

The Evolution of Art and Science

More often than not, the brilliant artistic outcomes of scientific studies have driven waves of creativity long after their making, influencing later discoveries, thought development, and cultural movements in both the arts and sciences.

When Goethe developed his thought on colour theory in the sixteenth century, he had likely been hopeful of its influence in the years to follow. Yet, it is highly improbable that he would have been able to predict how influential his thoughts would be to future of artistic movements, schools of teaching, and its fundamental influence work of one of the most prolific abstract artists of the twentieth century.

Had it not been for the historical oppression of women leading up to and during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, we may not have seen an influx in female botanists in the course of that period, and would not have had the groundbreaking botanical advances that much of our modern knowledge relies on. The cultural and artistic momentum opened doors for women in science, resulting in a wealth of brilliant scientific studies and the evolution of many modern illustrative styles.

Periodically benchmarked through differing aesthetics and technique, the stunning works of art and science document discoveries of a bygone age. They stand as beautifully articulated records of visual knowledge, showcasing the evolution of creative expression and scientific development.

While modern advancements provide a wealth of possibilities in both disciplines, the works forged in the intersection where the two subjects meet tell their own story of human existence, leaving a trail of thought and form unique to the period in which they were created. As technology continues to evolve, so will the interdependent worlds of science and art, inspiring each other in countless ways.

Discover the Art Meets Science Collection

-

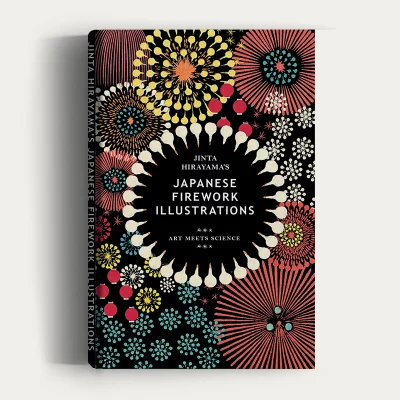

Art/Chemistry/Illustration/Japanese Woodblock/Pyrotechnics/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Chemistry/Illustration/Japanese Woodblock/Pyrotechnics/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageJinta Hirayama’s Japanese Firework Illustrations

£6.99 – £24.99Price range: £6.99 through £24.99 -

Nature/Botany/Illustration/Mushrooms/MycologySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Nature/Botany/Illustration/Mushrooms/MycologySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageAnna Maria Hussey’s Mushroom Illustrations

£7.99 – £29.99Price range: £7.99 through £29.99 -

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageMunsell’s Colour System

£7.99 – £25.99Price range: £7.99 through £25.99 -

Art/Astronomy/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Astronomy/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageUrania’s Star Charts

£7.99 – £29.99Price range: £7.99 through £29.99 -

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageEmily Vanderpoel’s Color Problems

£7.99 – £34.99Price range: £7.99 through £34.99 -

Animals/Butterflies & Moths/NatureSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Animals/Butterflies & Moths/NatureSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageMaria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosis

£9.99 – £34.99Price range: £9.99 through £34.99 -

Human Anatomy & Physiology/Life Sciences/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Human Anatomy & Physiology/Life Sciences/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageHenry Gray’s Anatomy

£9.99 – £39.99Price range: £9.99 through £39.99 -

Artists' Books/Individual Photographers/PhotographySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Artists' Books/Individual Photographers/PhotographySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageAnna Atkins’ Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns

£9.99 – £24.99Price range: £9.99 through £24.99 -

Life Sciences/Marine Biology/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Life Sciences/Marine Biology/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageErnst Haeckel’s Art Forms in Nature

£9.99 – £28.99Price range: £9.99 through £28.99 -

Geometry/MathematicsSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Geometry/MathematicsSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageOliver Byrne’s Elements of Euclid

£9.99 – £33.99Price range: £9.99 through £33.99 -

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageWerner’s Nomenclature of Colours

£9.99 – £22.99Price range: £9.99 through £22.99