Urania's MIrror: The Art of Astronomy

One of the oldest natural sciences in the world, astronomy has an enduring hold on human fascination. Stemming back to the first century, depictions of the night sky perforate cultures all around the world, rich in stunning artistic interpretation. Urania’s Mirror is a brilliant testament to thousands of years of celestial observation.

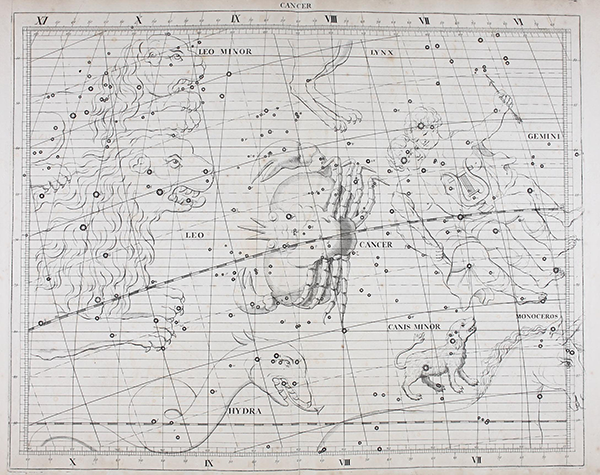

In these 32 beautifully illustrated cards, we find heavenly figures sprawled across the stars, encapsulating over 72 constellations in luminary form. The cards represent a long history of celestial cartography, where the myths and legends of centuries previous are brought to life.

Early Celestial Cartography

As the first humans explored the world, they sought to understand the skies above. While they mapped the constellations for practical purposes like navigation and farming, their understanding of the heavens was closely linked to the divine, with the stories of gods and goddesses informing their observations. The art of celestial cartography, or uranography, produced beautiful star maps, recording planets and stars from different points on the globe. These early maps were heavily based on astrological understanding, with folkloric beliefs at their centre, greatly influenced by each country’s culture. Founded on mediaeval manuscripts and mythological texts, key astromers like Ptolemy (85–165) and Al-Ṣūfī (903–986 AD) penned nomenclatures of the stars that encapsulated popular literary stories with the coordinates of the stars and planets they observed.

Such classical works were incredibly influential in the study of astronomy pre-fifteenth century, resulting in early star atlases that presented constellations formed around mythological narratives, brilliantly illuminated with figures and animals. They were continuously reimagined but often used outdated coordinates, and so misinterpreted the constellations as they existed in the skies above. Despite their beauty, many star maps became objects of fancy rather than being used for precise celestial understanding or navigation.

Uranometria

In the early 1600s, uranographer Johann Bayer (1572–1625) published Uranometria which changed the face of celestial cartography. Brilliantly illustrated, it was the first star atlas to cover the entire celestial sphere (rather than the traditional northern or southern hemisphere) and included a new system for star designation. As avant garde in its presentation as it was in its stellar nomenclature, Bayer presented twelve new constellations over 51 star charts, with each one laid out on individual pages. He categorised each star using the Greek alphabet, assigning the letter alpha (α) to the brightest star, and then each subsequent letter in order of descending brightness. As technology advanced, Bayer’s work represented a shift towards the sciences in astronomical illustration with his celestial atlas based on technical and observational data rather than literary narratives and outdated coordinates. It spurred a new scientific discourse that would go on to separate astronomy from its astrological beginnings.

John Flamsteed's 'Atlas Coelestis'

Following Bayer’s work, celestial atlases became immensely popular during the Age of Enlightenment (1685–1815). Many borrowed their iconography from the celestial figures found in many early Arabic atlases yet had westernised attributes that leant themselves to the Roman or Greek stories they were built on. When John Flamsteed’s groundbreaking Atlas Coelestis (1729) was published over a century after Bayer, the featured figures and animals echoed the styles of its predecessors.

Flamsteed (1646–1719) was the first Astronomer Royal at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. His work recording the constellations proved groundbreaking for the observatory, being the first astronomer to observe the planet Uranus, despite mistakenly cataloging it as a star. His atlas, published posthumously in 1729, was the first produced through telescopic observation. With his main motivation being to correct the errors presented in Bayer’s atlas, Flamsteed produced the largest and most comprehensive catalogue of its time, presenting 26 star maps of the constellations visible from London. Differing not only in its form, his illustrations chose to follow the Baroque aesthetic—a romantically stylised movement that was popular in Europe during the eighteenth century. Illustrated by James Thornhill (1675–1734), a renowned historical painter responsible for the murals on the inside of the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral, the constellation plates featured cherub-esque figures and idealised animals scattered among the stars. It was published using large imperial paper, twice the size of the atlases that came before, making it a highly esteemed publication in the world of astronomy.

19th Century Star Maps

Later on in the nineteenth century, fellow astronomer and celestial map maker Alexander Jamieson (1782–1850) developed Flamsteed’s work into a volume made for popular consumption. It was much smaller, being just larger than a standard book, making it more affordable to appeal to ameteur astronomers and enthusiasts alike. It followed the same layout as Flamsteed’s, with his atlas pages each individually mapped out on a grid, yet he only chose to only include stars that could be seen with the naked eye, making for a more compact volume. Within his Celestial Atlas (1822), Jamieson allowed himself more artistic freedom.

His figurative style differed again from the Baroque style of Flamsteed’s work, straying away from those inspired by classical iconography. His figures appear more realistic in their presentation yet the pages themselves are rich in beautiful detail. Each plate is hand coloured with light washes to accentuate the key constellations. A clear aesthetic choice by Jamieson, perhaps to appeal to a wider, modern, non-scientifc audience despite the work itself boasting an extensive and astronomically correct stellar nomenclature.

Urania's Mirror

Shortly after, Jamieson’s volume, Urania’s Mirror, was published in 1825. In a step away from the stellar nomenclatures of the previous years, it reimagined the astronomical illustrations for a more practical use. Similarly presented on individual cards, the second edition reimagined the heavens in brilliant colour, removing the embellishments, technical grids, and boundary lines that surrounded the constellations of Bayer, Flamsteed, and Jamieson. Set against a light blue wash background, the illustrations are almost identical to Jamieson’s in their form, yet they appear vibrantly full of life, with both human and animal draped in motion across the skies. Each card was perforated where the stars lay in the constellations, with the magnitude of each represented by the size of the hole punched into the cards. Once held up to the light, the user could easily see the constellations come to life.

While they were intended as parlour entertainment for the general public, they were entrenched with scientific understanding and presented an accurate view of the night sky. A written accompaniment, A Familiar Treatise on Astronomy by Jehoshaphat Aspin, was published by the same house in 1825, which included articulate descriptions for each plate, as well as general astronomical information regarding star projections, identifying the constellations, and the history of astronomy in the early nineteenth century. While this volume informed the user’s astronomical understanding, the cards themselves are captivating, illustrating the stories of the heavens in a blend of both the arts and sciences. Due to their tactile nature, few full sets of cards remain, with many being damaged when held too close to candle light.

Published in three editions between 1825 and 1834, the anonymous author of Urania’s Mirror was vaguely attributed to ‘a young lady’, but little other information regarding the illustrations was given. There was speculation as to who this young lady was, with fellow astronomers Mary Somerville (1780–1872) and Caroline Herschel (1750–1848) suggested, as well as the engraver Sidney Hall (1788–1831). It wasn’t until over a century later, however, that the identity of the maker was revealed to be English school master, Rev. Richard Rouse Bloxham (1765–1840), after a letter was found that outlined his involvement in the work. Perhaps the initial anonymity was a way to make the work appeal across the sexes, as was the style for publications during the period, or maybe it was a way to avoid plagarism due to the illustrative similarities to Jamieson’s atlas. Regardless of their origins, this collection of celestial cards are as enchanting as they were when they were first produced.

Urania’s Mirror remains a lynchpin in the history of celestial cartography. It represents a unique period of star atlas production, where ancient knowledge, folkloric narratives, and groundbreaking science met. Following its publication, the technology surrounding astronomy surged, and such creative efforts of documenting the heavens fell behind scientific observation. While these more modern expositions of the night skies held their own beauty, they leant further into the academic realm, often disregarding the romantic, astrological beginnings. The beautifully illustrated cards of Urania’s Mirror showcase thousands of years’ worth of astronomical observation through its vibrant forms and figures. An artefact of celestial cartography unlike any other, it is a truly stunning example of where the arts and sciences collide.

More from the Art Meets Science Journal

the art meets science collection

-

Art/Chemistry/Illustration/Japanese Woodblock/Pyrotechnics/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Chemistry/Illustration/Japanese Woodblock/Pyrotechnics/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageJinta Hirayama’s Japanese Firework Illustrations

£6.99 – £24.99Price range: £6.99 through £24.99 -

Nature/Botany/Illustration/Mushrooms/MycologySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Nature/Botany/Illustration/Mushrooms/MycologySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageAnna Maria Hussey’s Mushroom Illustrations

£7.99 – £29.99Price range: £7.99 through £29.99 -

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageMunsell’s Colour System

£7.99 – £25.99Price range: £7.99 through £25.99 -

Art/Astronomy/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Astronomy/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageUrania’s Star Charts

£7.99 – £29.99Price range: £7.99 through £29.99 -

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageEmily Vanderpoel’s Color Problems

£7.99 – £34.99Price range: £7.99 through £34.99 -

Animals/Butterflies & Moths/NatureSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Animals/Butterflies & Moths/NatureSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageMaria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosis

£9.99 – £34.99Price range: £9.99 through £34.99 -

Human Anatomy & Physiology/Life Sciences/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Human Anatomy & Physiology/Life Sciences/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageHenry Gray’s Anatomy

£9.99 – £39.99Price range: £9.99 through £39.99 -

Artists' Books/Individual Photographers/PhotographySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Artists' Books/Individual Photographers/PhotographySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageAnna Atkins’ Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns

£9.99 – £24.99Price range: £9.99 through £24.99 -

Life Sciences/Marine Biology/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Life Sciences/Marine Biology/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageErnst Haeckel’s Art Forms in Nature

£9.99 – £28.99Price range: £9.99 through £28.99 -

Geometry/MathematicsSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Geometry/MathematicsSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageOliver Byrne’s Elements of Euclid

£9.99 – £33.99Price range: £9.99 through £33.99 -

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageWerner’s Nomenclature of Colours

£9.99 – £22.99Price range: £9.99 through £22.99